The Perforated Path to Computing: Paper Tape and the Birth of Software Patching

How early engineers stored, edited, and debugged code with scissors, tape, and raw binary precision.

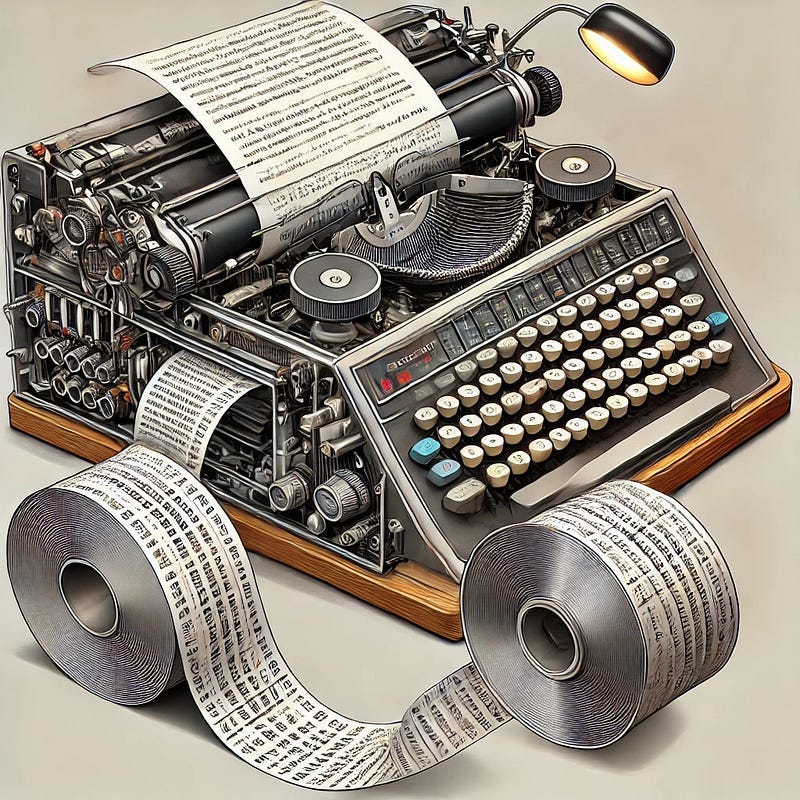

Before solid-state drives, magnetic disks, or even magnetic tape, the earliest digital computers relied on a deceptively simple yet profoundly effective medium: paper tape. Composed of narrow strips of perforated paper or Mylar, paper tape stored binary data through hole patterns — each punched row a byte or instruction, each channel a bit. But behind this analog-feeling technology was a rigorously structured and surprisingly versatile system that allowed machines to load, store, and execute programs at a time when RAM was scarce, CPUs were room-sized, and even “volatile memory” had a literal meaning.

Let’s take a technical look at how paper tape worked, and explore a particularly delightful legacy from that era: the original and very literal meaning of “patching” software.

Why Paper Tape?

Paper tape satisfied several requirements in early computing:

Non-volatility: Unlike early DRAM and register banks, paper tape retained data without power.

Portability: Tapes could be physically transported between labs and machines.

Low cost: Easier and cheaper to duplicate and distribute than core memory.

Simplicity: Mechanically read with low-tech devices like spring-loaded pins or light sensors.

Early memory was measured in kilobytes (if you were lucky), and storage was a luxury. As such, paper tape served as both primary program input and external data storage, supporting batch computing workflows.

Tape Formats and Encoding

Channels and Tracks

A paper tape was organized into parallel tracks (or channels) punched across the tape width.

The common formats were:

5-channel tape: For Baudot and early teletypes, encoding 32 characters.

6-channel tape: Expanded to allow uppercase/lowercase distinctions.

8-channel tape: Aligned with ASCII and EBCDIC standards. The IBM 8-bit ASCII tape became a standard for general computing.

Physical Structure

Tape Width: Typically 1 inch for 8-channel tapes.

Hole Pitch: 0.1 inch between columns, matching early IBM hardware tolerances.

Sprocket Holes: Centered between data tracks 2 and 3, used for tape feed synchronization.

Orientation Notching: Operators cut a triangle on the leader end to indicate directionality.

Readers and Punches

Mechanical readers: Used contact pins that dropped into holes and closed circuits.

Opto-electronic readers: More advanced; used photodiodes to detect light through holes.

Tape punches: Included standalone units and Teletype ASR devices (e.g., Model 33) which punched and printed in parallel.

Readers synchronized based on sprocket holes and could achieve speeds from 50 cps (characters per second) up to 1000+ cps in high-speed optical models.

Bootstrapping and Execution

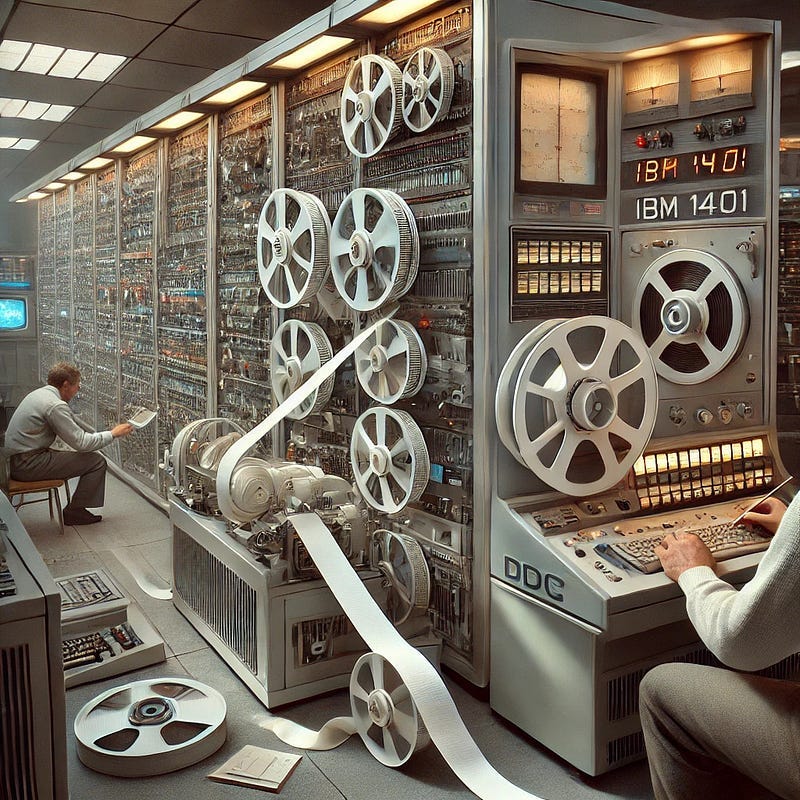

Early computers did not contain ROM or onboard firmware. Programs were typically loaded via a bootloader entered through switches, which then instructed the machine to load a full program via paper tape.

This process worked as follows:

Enter minimal machine code using toggle switches on a front panel.

Execute the bootstrap routine to read paper tape into memory.

Begin execution of the now-loaded program.

Literal Software Patching: The Tape Era

Here’s where it gets fun — and historical. The term “software patch” originates directly from paper tape computing.

The Problem: Inflexibility

Tapes were sequential and linear. If an error existed at byte 43 of a 1000-byte program, you couldn’t just edit byte 43.

You had to:

Punch an entirely new tape (tedious), or

Patch the original tape.

The Technique: Tape-on-Tape Surgery

Engineers would take a small piece of opaque tape (often Scotch tape or mylar patches) and physically cover the offending hole(s), effectively converting a ‘1’ back into a ‘0’. Then, new holes could be punched through the tape to overwrite with corrected data.

This procedure gave rise to the term “patching” a program — literally covering over old code and applying new instructions in place.

Over time, the term “software patch” came to describe any fix or update applied to software, even as the physical practice of tape patching faded into digital abstraction.

An engineer from that era might keep a “patch kit” at their desk — complete with scissors, correction tape, and a precise hole punch tool. Debugging meant line-by-line visual inspection, aligning tape with reference overlays, and manually correcting data at the bit level. “He who patches fastest, computes longest,” as one might say in jest.

Batch Processing and Teletype Integration

Given the time-consuming nature of manual input, most paper tape programs were authored offline using a teleprinter or teletype, which could:

Print to screen or paper,

Punch a corresponding paper tape, and

Read tape for re-input later.

Computing facilities often had rows of teletypes for simultaneous operator use. Completed tapes were queued in batch mode: operators would collect jobs, feed them sequentially into the mainframe, and return output days later.

Legacy and Impact

The influence of paper tape extends far beyond its physical form:

80-column displays: Mirrored the 80-column punched card format.

Control characters like BEL (bell), CR (carriage return), and LF (line feed) have lineage in tape-based teletypes.

Batch systems and early operating systems such as DEC’s RT-11 supported tape I/O natively.

Software patches still carry the etymological fingerprint of physical tape repair.

Today, the only places paper tape still see occasional use are:

CNC machines with legacy interfaces,

High-EMI industrial zones, where magnetic media fails,

And, occasionally, military and aerospace systems designed decades ago.

Conclusion: From Perforation to Abstraction

In an era when computing required mechanical ingenuity, the paper tape was a marvel: an elegant blend of simplicity, durability, and technical power. Though long superseded by magnetic and solid-state storage, its legacy endures — not only in terminology, but in the fundamental patterns of programming workflows.

Next time you hear about a “hotfix” or “security patch,” give a nod to those pioneers who — armed with nothing more than tape, scissors, and patience — pioneered the art of debugging, one literal patch at a time.

You can sign up to receive emails each time I publish.

Link to the original Bitcoin White Paper: White Paper:

Dollar-Cost-Average Bitcoin ($10 Free Bitcoin): DCA-SWAN

Access to our high-net-worth Bitcoin investor technical services is available now: cccCloud

“This content is intended solely for informational use. It is not a substitute for professional financial or legal counsel. We cannot guarantee the accuracy of the information, so we recommend consulting with a qualified financial advisor before making any substantial financial commitments.