Bitcoin's Full-Stack Threat Model: Security Risks from Consensus to Wallet

A Comprehensive Analysis of Protocol, Network, and Application-Level Attack Surfaces in Bitcoin

Bitcoin’s Attack Surface: A Comprehensive Threat Model from Node to Wallet

The dominant threat model in popular Bitcoin discourse tends to begin and end with seed phrase security. While protecting key material is foundational, it’s not remotely sufficient. Bitcoin is a multi-layered protocol with surfaces exposed across networking, consensus, software, and user interfaces. If your node is compromised, your keys don’t matter. If your wallet leaks metadata, your privacy is lost. Subverting the protocol invalidates your economic assumptions.

This piece maps the entire attack surface—from the P2P layer to derivation path bugs—and outlines how Bitcoiners can harden their stacks across each vector.

I. Full Node-Level Threats

The full node is the root of trust in Bitcoin. It independently verifies the rules, filters invalid data, and enforces your view of consensus. If the node experiences deception, degradation, or isolation, it also affects you.

1. Eclipse Attacks

An eclipse attack occurs when an attacker isolates a full node by monopolizing all of its inbound and outbound peer connections. Once isolated, the attacker can feed the victim manipulated block and mempool data, delay transaction propagation, or even trick the node into accepting a reorg or invalid chain.

This technique was formalized by Heilman et al. in 2015. The attack exploited Bitcoin Core’s unstructured peer selection logic and lack of peer authentication.

To mitigate this, node operators should enable Tor-only connections-onlynet=onion, restrict the number of inbound peers from any given /16 subnet, and use the anchor peer system introduced in Bitcoin Core 0.21+. Running over I2P or using VPNs with manual peer lists also helps diversify the network layer.

2. BGP Hijacking

Bitcoin traffic over clearnet is subject to the same routing weaknesses that affect the broader internet. BGP hijacks allow attackers to redirect node traffic at the ISP level, potentially intercepting or censoring data.

Historical BGP hijacks affecting AWS and Google in 2017 showed how trivial this type of attack can be. While Bitcoin’s peer-to-peer gossip protocol mitigates some of the impact, the potential for censorship or deanonymization persists.

The primary mitigation is to route your full node traffic through Tor or I2P exclusively. Alternatively, running a Blockstream Satellite receiver provides consensus data independent of the internet entirely.

3. Sybil Attacks and Poisoned Peers

A Sybil attack involves flooding the network with dishonest nodes. These peers could stifle the spread of Bitcoin, spam invalid data, or contaminate address lists.

Bitcoin is not consensus-Sybil resistant—PoW does that—but the P2P layer is still vulnerable. Bitcoin Core now limits peers from similar IP ranges and maintains an internal reputation system for peers.

Mitigation includes using the -asmap feature to avoid peers from the same autonomous system, maintaining a curated list of trusted nodes, and watching logs for unusual patterns in peer behavior.

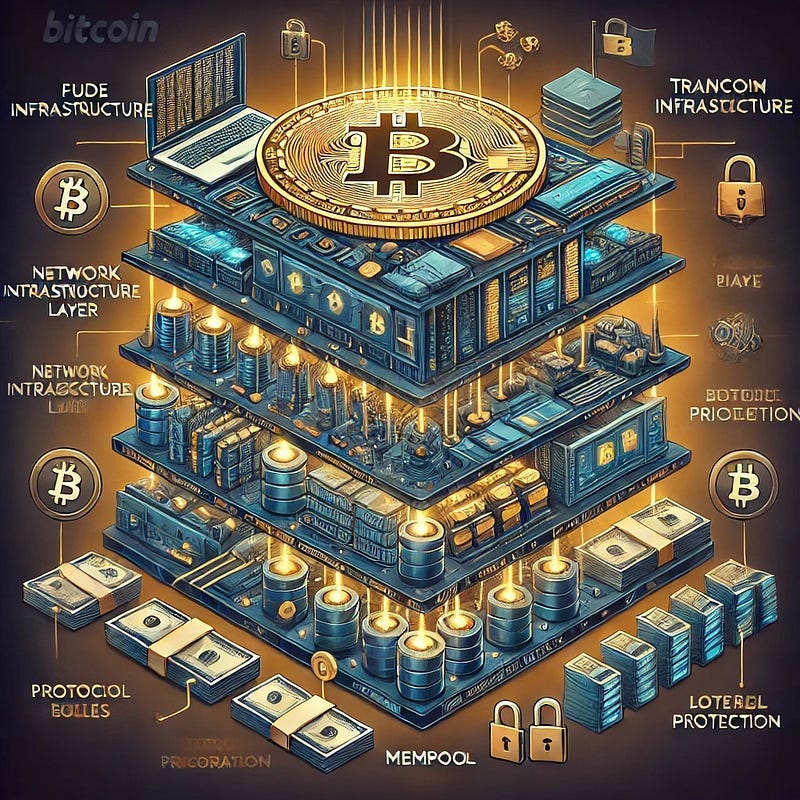

II. Transaction-Level Threats

Even assuming a hardened node, broadcasting or receiving Bitcoin transactions involves its set of risks—particularly at the mempool and fee market layers.

1. Replace-by-Fee (RBF) Exploits

RBF, formalized in BIP 125, allows users to resend unconfirmed transactions with higher fees. While useful for fee bumps, it enables pre-confirmation double-spend attempts in merchant or ATM contexts.

The original “first-seen” rule was deprecated to allow more flexible fee markets, but the tradeoff is clear: unconfirmed transactions cannot be trusted in adversarial settings.

Merchants should never consider zero-conf RBF-enabled payments as final. Instead, use systems that monitor the mempool for conflicts, delay fulfillment until at least one confirmation, or use Lightning with watchtower infrastructure for real-time fraud detection.

2. Dusting Attacks

In dusting attacks, adversaries send tiny UTXOs (often <546 sats) to wallets in an attempt to deanonymize users. When the wallet later consolidates the dust with other UTXOs, heuristics can link otherwise distinct clusters.

To counter this, wallets should offer coin control and allow UTXO labeling. Dust should be flagged and avoided in spend selection logic. Users can also run separate wallets for receiving vs. spending, segmenting potential exposure.

3. Fee Sniping

In a high-fee environment, a miner may find it profitable to reorg the chain by one or two blocks to capture a lucrative transaction that was confirmed by a competitor.

Despite the absence of such an attack in the wild, it still poses a latent economic threat.

One mitigation is to randomize nLockTime transactions, introducing uncertainty around their reorg value. Wallets can also break up high-value payments into batches or introduce time delays to reduce salience in the mempool.

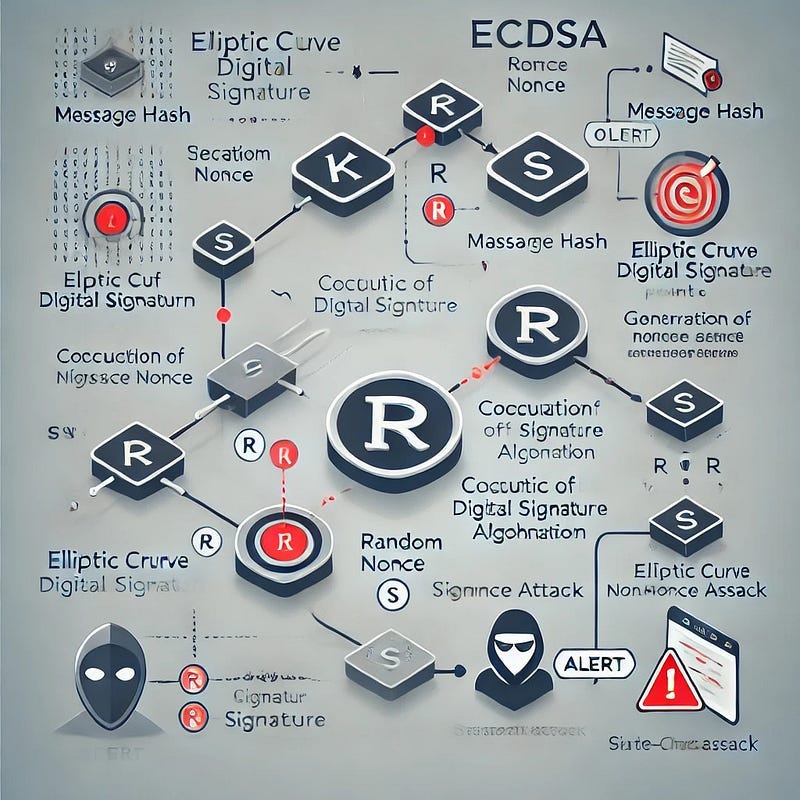

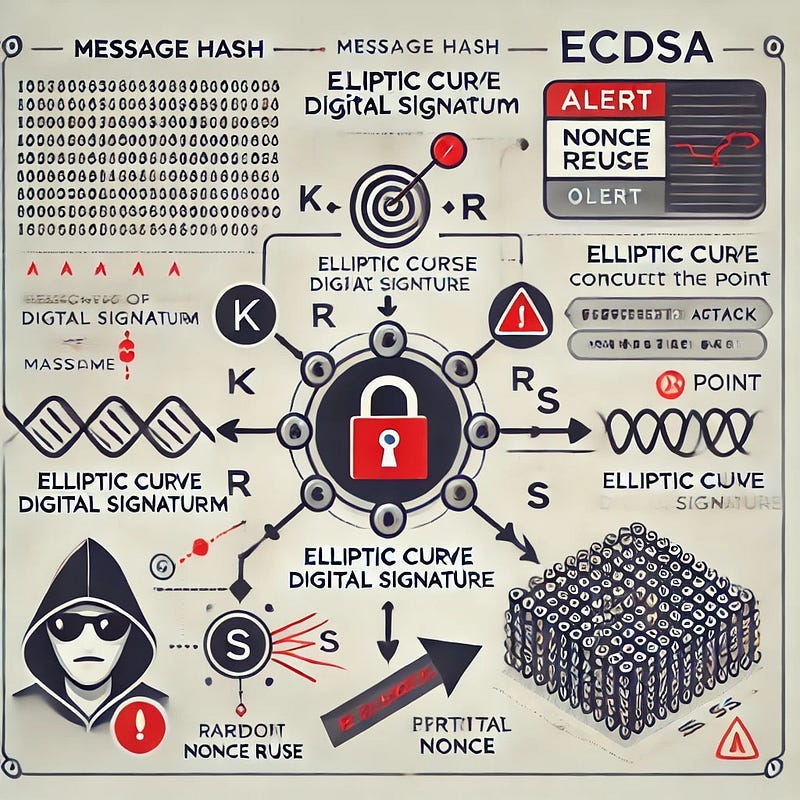

III. Wallet-Level Threats

The wallet—either hardware or software—is the layer where most users interact with Bitcoin. Additionally, it's the layer most susceptible to compromise.

1. Supply Chain Attacks

Wallet software can be compromised during compilation, firmware updates, or distribution. Malware has been injected into clones of Electron Cash and Electrum in the past. A breach at Ledger exposed customer PII, potentially leading to phishing or in-person threats.

Mitigation requires reproducible builds, which ensure that binaries can be independently verified. Always verify PGP signatures from maintainers and avoid wallets that force firmware updates or operate closed source. Use air-gapped devices for signing where possible and rely on PSBT workflows to isolate key handling.

2. Metadata and Network Leakage

Many wallets leak data through clearnet connections to third-party APIs (e.g., block explorers) or by exporting xpubs for convenience. These leaks allow adversaries to reconstruct wallet balances, UTXO history, and even spending behavior.

The solution is to use wallets that connect directly to your full node over Tor—e.g., Sparrow Wallet with a Tor-routed Bitcoin Core or Electrum server. Avoid exporting xpubs unless absolutely necessary. When using watch-only wallets, ensure that the derivation path and address index are documented, and never share access to a full xpub tree.

3. Derivation Path Inconsistencies

Most modern wallets use BIP-32 HD keys, but the derivation standards vary: BIP-44 for legacy addresses, BIP-49 for nested segwit, and BIP-84 for native segwit.

Wallets that don’t document their path choices may create backups that are incompatible across software. Worse, mismatched paths can render funds inaccessible after restoration.

Users must always document the exact derivation path used (m/84'/0'/0'/0/x, for example). When possible, use descriptor-based wallets, which encode paths and script types explicitly. Descriptors also improve interoperability across wallets and eliminate ambiguity around script policies.

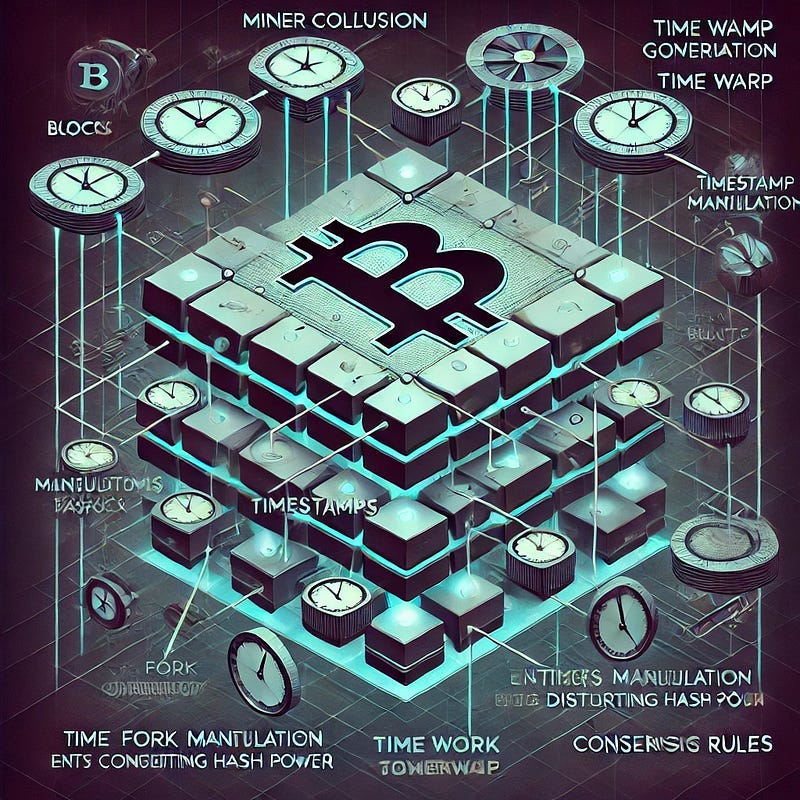

IV. Consensus and Protocol-Layer Threats

Bitcoin’s consensus layer is intentionally rigid—but not immune. Attackers may try to subvert rules through time manipulation, collusion, or political coercion via soft forks.

1. Time Warp Attacks

Bitcoin’s difficulty adjustment relies on block timestamps. Miners can manipulate timestamps to skew the adjustment algorithm, either slowing or speeding up difficulty recalibration.

Historically, early pools theorized and partially observed this attack, delaying timestamp submission to gain a competitive edge. To harden the system, early pools introduced mitigations like BIP 113 and Bitcoin Core's time drift checks, which limit future timestamps to two hours beyond MTP.

The best defense today remains strict timestamp validation and monitoring for unusual intervals between blocks during adjustment epochs.

2. Miner Collusion and Censorship

Mining pools have economic incentives to censor transactions—whether due to regulation (e.g., OFAC compliance) or strategic targeting. In 2021, Marathon announced its intention to filter transactions; however, it later reversed this policy in response to backlash.

Miners could theoretically collude to censor transactions, enforce a specific mempool policy, or reject blocks not meeting political criteria.

To defend against this, the ecosystem must move toward Stratum v2, which gives individual miners control over block templates, reducing central control by pool operators. The presence of economically active nodes rejecting censored chains is also essential.

3. Soft Fork Coercion

Soft forks are backwards-compatible changes to consensus rules. While technically safe for non-upgrading nodes, soft forks can be politically coercive—activating changes without true economic consensus.

The SegWit activation battle in 2017 highlighted this dynamic. The resolution came through BIP 148 (UASF), where users enforced the fork against mining resistance.

Node operators must retain the ability to enforce their consensus rules. Always review proposed soft forks (via BIPs), follow discussions in dev mailing lists, and run the software that aligns with your desired rule set. Economic consensus is a social layer defense, not a technical one.

Conclusion

Bitcoin’s security model spans more than private keys and seed phrases. A comprehensive threat model must include eclipse resistance, transaction propagation integrity, wallet software hygiene, and consensus sovereignty. These layers are interdependent—failures in any one can compromise the others.

Security isn’t a product; it’s an operational discipline. Harden your node. Scrutinize your wallet stack. Don’t broadcast on the clearnet. Know your derivation path. Run your own software, with your own rules.

Bitcoin is adversarial by design. So act like it.

You can sign up to receive emails each time I publish.

Link to the original Bitcoin White Paper: White Paper:

Dollar-Cost-Average Bitcoin ($10 Free Bitcoin): DCA-SWAN

Access to our high-net-worth Bitcoin investor technical services is available now: cccCloud

“This content is intended solely for informational use. It is not a substitute for professional financial or legal counsel. We cannot guarantee the accuracy of the information, so we recommend consulting a qualified financial advisor before making any substantial financial commitments.